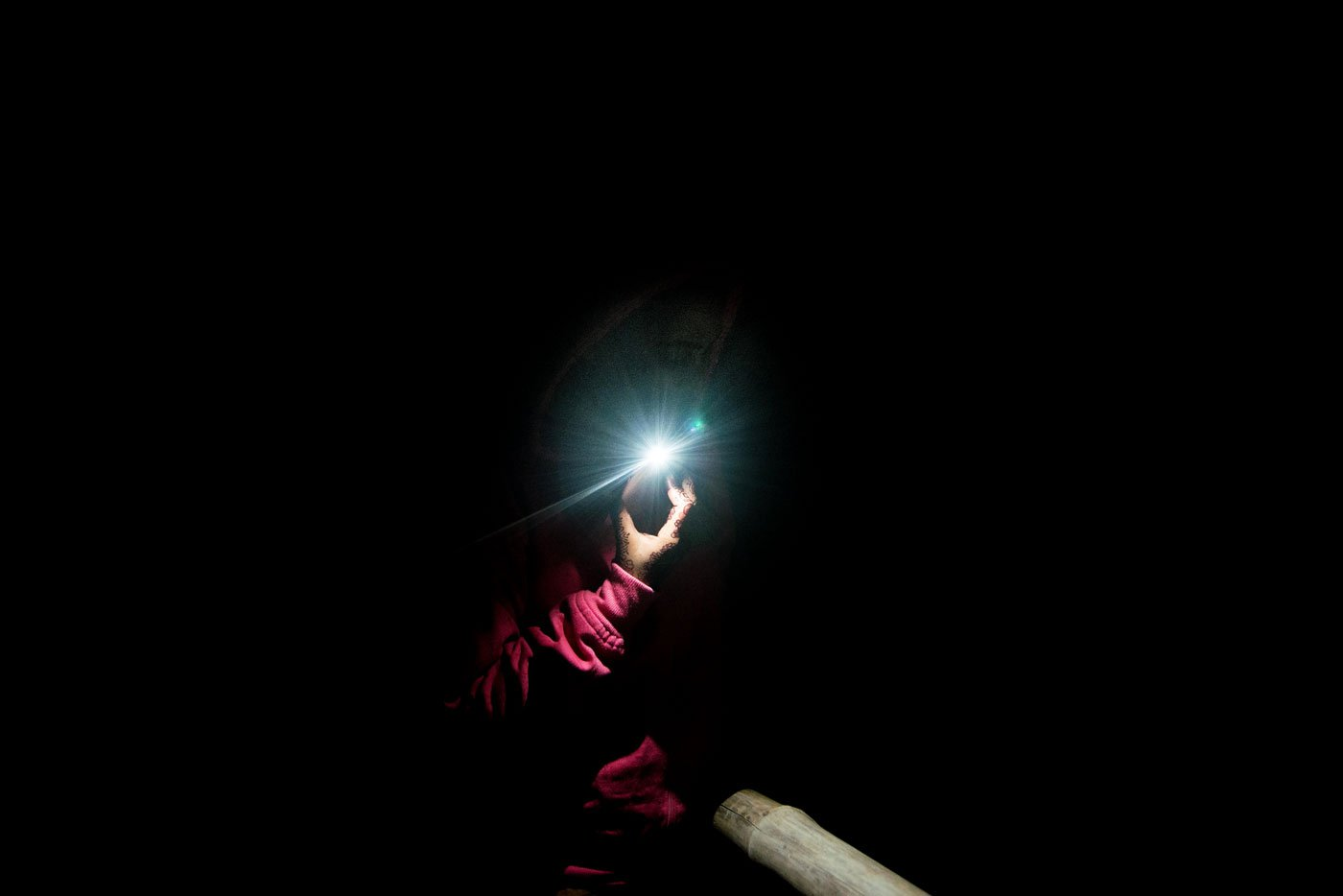

Illustration by Labani Jangi

Published in People's Archive of Rural India. 10 March 2022

All of 22 and already worn down by health problems for over three to four years, as Meenu Sardar stepped out to fetch water that summer morning in 2021, nothing could have warned her that the worst was about to come. The stepway leading to the pond in Dayapur village was broken in places. Meenu slipped and tumbled down the stairs, falling face down.

“I had excruciating pain in my chest and stomach,” she recounts in Bengali . “I started bleeding from the vagina. When I went to the bathroom, something slipped out of me and fell to the floor. I noticed a flesh-like substance coming out of me. I tried to pull it out, but I couldn’t extract the whole thing.”

A visit to a private clinic in a nearby village confirmed the miscarriage. Meenu, tall, thin, and wearing a smile despite her worries, had irregular menstrual cycles since then, along with acute physical pain and emotional distress.

Her village in the Gosaba block of West Bengal’s South 24 Parganas district has a population of about 5,000. Lush with sprawling paddy fields and the mangrove forests of the Sundarbans, it is among only a handful of interior villages in Gosaba that are connected by road.

Meenu was bleeding without a break for more than a month after the fall, and that was not the end of her suffering. “Sharirik somporke eto byatha kore [sexual intercourse is so painful],” she says. “It feels as if I am being torn apart. When I have to pass stools and exert pressure, or when I lift heavy objects, I can feel my uterus coming down.”

Circumstances and conditioning deepened her misery. On suffering vaginal bleeding after the fall, Meenu, who did not study beyond Class 10, decided not to consult the ASHA worker (Accredited Social Health Activist) in Dayapur. “I didn’t want her to know,” she says, “because others in my village might have come to know about my miscarriage. Also, I don’t think she would have known what to do.”

She and her husband, Bappa Sardar, had not been planning a baby, but she was not using any contraception at the time. “I didn’t know about family planning methods when I got married. Nobody told me. I learnt about them only after I miscarried.”

Meenu is aware of the sole woman gynaecologist posted at the Gosaba Rural Hospital, about 12 kilometres from Dayapur, but she was never available. There are two Rural Medical Practitioners (RMPs), unlicensed healthcare providers, in her village.

Dayapur’s RMPs are both men.

“I was not comfortable disclosing my problem to a man. Also, they don’t have expertise,” she says.

Meenu and Bappa visited several private doctors in the district, and one in Kolkata too, spending more than Rs. 10,000, but with little luck. The couple’s only source of income is Bappa’s salary of Rs. 5,000 from a small grocery store where he works. He borrowed from friends to pay for the medical consultations.

A course of pills from a homeopath in Dayapur restored her menstrual cycle eventually. She says he was the only male doctor she felt comfortable discussing her miscarriage with. An abdominal ultrasound that he advised to diagnose her continuing vaginal discharge and acute discomfort will have to wait until Meenu has saved enough money.

Until then, she cannot lift heavy objects, and has to frequently rest.

Meenu’s circuitous route to access healthcare is a common narrative among women in villages of the region. A 2016 study on health system actors in the Indian Sundarbans says residents here lack choices in healthcare. Publicly funded facilities are “either non-existent or non-functional”, and the functional facilities may be physically inaccessible due to the terrain. Filling this gap is an army of informal healthcare providers, “the only resort in normal times as during climatic crisis,” notes the study, which examines the social network of RMPs.

*****

This was not Meenu’s first nagging health problem. In 2018, she suffered from an itchy rash all over her body. As angry red boils covered her arms, legs, chest and face, Meenu could feel her arms and legs swelling. The heat worsened the itching. The family spent nearly Rs. 20,000 on doctor consultations and medicines.

“For more than a year, this was my life – just going to hospitals,” she says. Recovery was slow, leaving her with a persistent fear that the skin ordeal may return.

Less than 10 kilometres from where Meenu lives, 51-year-old Alapi Mondal in Rajat Jubilee village recounts a strikingly similar story. “Three or four years ago, I suffered intense itching all over my skin, sometimes so severe that there would be pus oozing out. I know many other women who suffered the same problem. At one point, every family in our village and the adjoining villages had someone whose skin was infected. The doctor told me it was some kind of a virus.”

Alapi, who is a fisherwoman, is better now, having been on medication for nearly a year. She was able to consult doctors at a charitable private clinic in Sonarpur block at only Rs. 2 per visit, but the medicines were expensive. Her family spent Rs. 13,000 on her treatment. Visiting the clinic involved a journey of 4-5 hours. Her own village has a small government-run clinic, but she didn’t know about its existence then.

“After my skin problems worsened, I stopped going to fish,” she says. Earlier, she used to wade off the riverbank, often neck-deep in water for hours, dragging her net behind her for tiger prawn seedlings. She never resumed working.

Several women in Rajat Jubilee have experienced skin conditions, for which they blame the highly saline water of the Sundarbans.

In an essay on the impact of the water quality on local livelihood, in the book Pond Ecosystems of the Indian Sundarbans , author Sourav Das writes that women suffer skin diseases from using saline pond water for cooking, bathing and washing. Prawn seed farmers spend 4-6 hours a day in saline river water. “They also suffer from reproductive tract infection by the use of saline water,” he notes.

Research has shown that the abnormally high salinity of water in the Sundarbans is on account of rising sea levels, cyclones and storm surges – all portents of climate change – in addition to shrimp farming and reduced mangrove cover. Salt water contamination of all water resources, including drinking water, is typical to the large river deltas in Asia.

“In the Sundarbans, the high salinity of water is one of the major causes of gynaecological problems, especially a high rate of pelvic inflammatory disease,” says Dr. Shyamol Chakraborty, who practises at Kolkata’s R.G. Kar Medical College and Hospital and has conducted medical camps across the Sundarbans. “But salt water is not the only reason. Socio-economic status, ecology, the use of plastic, hygiene, nutrition and healthcare delivery systems all play an important role.”

According to Dr. Jaya Shreedhar, senior health media advisor to Internews, an international media support organisation, women in this region are exposed to saline water for 4-7 hours a day, particularly the shrimp farmers. They are vulnerable to a host of afflictions including dysentery, diarrhoea, skin diseases, cardiovascular diseases, abdominal pain and gastric ulcers. Saline water may lead to hypertension, especially in women, affecting pregnancies, and sometimes causing miscarriages.

Among people in the 15-59 age group in the Sundarbans, women have a disproportionately higher burden of ailments than the men, observed a study in 2010.

Anwarul Alam, coordinator of a mobile medical unit run by Southern Health Improvement Samity, an NGO in South 24 Parganas providing medical services in remote areas, says their travelling medical unit receives 400-450 patients a week in the Sundarbans. About 60 per cent are women, many with skin complaints, leucorrhoea (vaginal discharge), anaemia and amenorrhoea (absence of or irregular menstruation).

Alam says the women patients are malnourished. “Most fruits and vegetables are brought by boat to the islands and not locally grown. Not everybody can afford them. The increasing heat during summers and shortage of fresh water is also a major cause of ailments,” he says.

Meenu and Alapi eat rice, dal , potatoes and fish on most days. They eat few fruits and vegetables as they do not grow them. Like Meenu, Alapi too has multiple maladies.

About five years ago, Alapi experienced excessive bleeding. “I had to undergo three surgeries to get my jarayu [uterus] removed after a sonography revealed a tumour. My family must have spent more than 50,000 rupees,” she says. The first surgery was to remove an appendix, and the other two were for a hysterectomy.

It was a long journey to the private hospital, located in Sonakhali village of the neighbouring Basanti block, where Alapi’s hysterectomy was performed. She had to take a boat from Rajat Jubilee to the ferry ghat in Gosaba, another boat to the ferry ghat in Gadhkhali village, and from there a bus or shared van to Sonakhali – the entire journey took 2-3 hours one way.

Alapi, who has a son and a daughter, knows at least four or five other women in Rajat Jubilee who underwent total hysterectomies.

One of them is Basanti Mondal, a 40-year-old fisherwoman. “The doctors told me my uterus had a tumour. Earlier, I had a lot of energy to go fishing. I could work very hard,” says the mother of three. “But I don’t feel as energetic after my uterus was removed.” She paid Rs. 40,000 for the surgery at a private hospital.

The National Family Health Survey-4 (2015-16) noted that 2.1 per cent of women aged 15 to 49 years in rural West Bengal had undergone hysterectomies – marginally higher than the urban West Bengal rate of 1.9 per cent. (The all-India rate was 3.2 per cent.)

In an article published in the Bengali daily Anandabazar Patrika in September last year, journalist Swati Bhattacharjee writes that in the Sudarbans, women as young as 26-36 years have undergone the surgery to remove their uterus after complaining of vaginal infection, excessive or irregular bleeding, painful sexual intercourse or pelvic inflammation.

Unqualified medical practitioners scare these women of having uterine tumours and subsequently into undergoing a hysterectomy at a private hospital. According to Bhattacharjee, profiteering private clinics take advantage of the state government’s Swasthya Sathi insurance scheme that provides a cover of up to Rs. 5 lakh annually for beneficiary families.

For Meenu, Alapi, Basanti and millions of other women in the Sundarbans, sexual and reproductive health problems are compounded by the difficulties in accessing healthcare.

Basanti travelled five hours from her home in Gosaba block for her hysterectomy. “Why can’t the government have more hospitals and nursing homes? Or even more gynaecologists?” she asks. “Even if we are poor, we don’t want to die.”

The names of Meenu and Bappa Sardar, and their location, have been changed to protect their privacy.

Read the original article: https://ruralindiaonline.org/en/articles/i-didnt-want-others-to-know-i-had-miscarried/