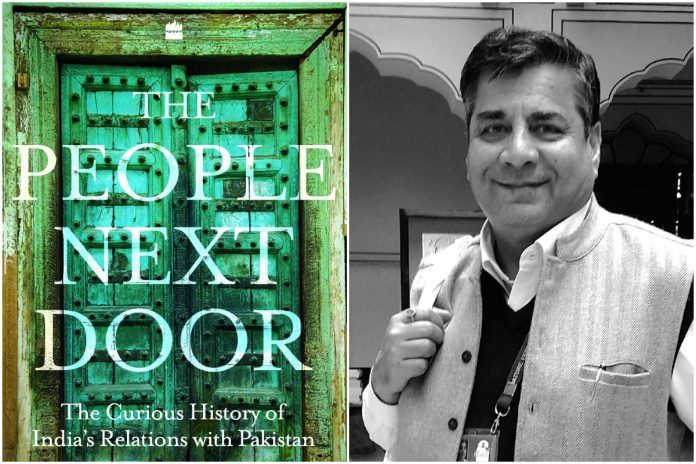

People Next Door, book cover and the author TCA Raghavan

Published in The Print. 23 December 2017

The India-Pakistan story has seen multiple iterations, told from various perspectives. Reams of literature have scrutinised the relationship, whether the layers of ties between the people or bilateral issues between the governments. Various authors have written about rifts and wars caused by disputes over land and water or spoken about the common grounds of history, language, sport and culture. We have had hardnosed militaristic analyses and conciliatory peace perspectives. Beyond this, can one have anything new to add?

This is where T.C.A. Raghavan’s work, intriguingly titled The People Next door. The Curious History of India’s Relations with Pakistan comes in. Raghavan who was the deputy high commissioner in Islamabad from 2003 to 2007 and high commissioner from 2013 to 2015, finds the gaps and spaces in the telling of well-known historical events, bringing to light little known and curious aspects of the relationship.

The heads of states and foreign ministers who decided the course of history were not just names but real people with idiosyncrasies and prejudices, in Raghavan’s telling. Pakistan’s military rulers like Ayub Khan and Zia-ul-Haq are not evil incarnate, but people who tried in their own way to resolve differences between the two countries. Therefore, we are told that Ayub Khan could have taken advantage by attacking India during the 1962 war with China, but chose not to. We learn about the great personal camaraderie between Morarji Desai and Zia-ul-Haq, but also about the subsequent coldness between Indira Gandhi and Zia. We also receive an account of Track-II peace efforts and the fate of these initiatives.

As Indians, we are aware of the different views within the country on Pakistan. But how do Pakistanis view India? This is also where the book succeeds — in repeatedly holding up mirror images of the two peoples and how both view each other, rather than offering only a one-sided view of history. The author constantly evokes the title of his book through the course of chapters — we are constantly made aware of us and them of us — the people next door, staring at each other from close quarters but hopelessly distant and separated.

In times of hyper nationalism, Raghavan’s is a measured voice of balance which gives us a view of what was happening behind the curtains of official history and formal motions of diplomacy on both sides. His account of the Bangladesh war of independence and its very different impacts on India and Pakistan make us aware of how crushing it was for Pakistan and how at diplomatic forums like the United Nations, Indian delegates were instructed by Swaran Singh to not display triumphalism.

Raghavan attempts to show to us the flesh and blood of the relationship than just mapping the skeleton. How did people interpret the meaning of Partition in their lives? The fate of properties and belongings left behind when choosing the other country as home is exemplified in the story of ‘Bombay’s Jinnah House’ owned by Pakistan’s founder Mohammed Ali Jinnah. Who should have legitimate claims to it? The daughter of Jinnah who lived in India, his sister who lived in Pakistan, or the government of India or Pakistan?

Raghavan reminds us that the business of Partition had to be conducted too — the mass flows of people, administration of Hyderabad, Junagadh and Kashmir, division of territories and water bodies. He writes that the two governments had to work closely together and after the horrific violence of Punjab, were concerned about how the flows of people between the erstwhile East Pakistan and West Bengal could be peaceful.

Harking back to another era, we are taken to a time when it was possible for thousands to travel to Lahore to watch a test match and for the governor general of Pakistan, Malik Ghulam Muhammad, to be present at India’s 1955 Republic Day celebrations. We are also made privy to the awkward episode of the high commissioner Kewal Singh attending the wedding reception of the son of Pakistan’s finance minister in Rawalpindi, coinciding with the outbreak of the 1965 war. The war was indeed a turning point in ties. Travel ceased and getting a visa became a herculean task. The ups and downs would thus continue over the decades.

Raghavan’s book provides us a wide angle view of India-Pakistan relations and ought to be read by anyone interested in a humanist narration of ties between the two countries, told with a good dose of empathy.

Read the original article: https://theprint.in/pageturner/afterword/people-next-door-provides-wide-angle-view-india-pakistan-relations/24466/